Galanos

War Story: First Impressions

01 August 2005

Louis Galanos

The Army had trained me as a radio operator and I had every expectation that they would assign me to a unit in need of one. When I arrived in Qui Nhon I was sent to the Headquarters Company of the US Army Support Command in Qui Nhon. My assignment was that of clerk typist.

It seems that, at the time, the Army had a surplus of radio operators but a shortage of clerk typists. It's a fact that the Army actually runs on paper and ink, not gas and diesel. I knew how to type because I took a class in high school and also radio operators were trained to type in order to operate some of the more sophisticated radios.

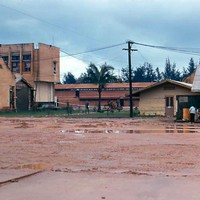

US Army Support Command HQ in Qui Nhon

The headquarters company compound was within walking distance to Hoang Hau Beach at Qui Nhon Harbor and Vung Lang Mai Bay on the South China Sea. Across the street from the compound was the city of Qui Nhon with civilian residences, shops, restaurants, and other businesses that tried to cater to the American soldier.

There were a lot of first impressions for a naïve 21-year-old soldier just new to Vietnam in 1966. One of those was seeing a middle-aged Vietnamese woman walking toward me on a dirt city street, stopping to put down her package, then rolling up the leg of her baggy black silk pants, then squatting down to urinate right there in front of everyone. Only later did it dawn on me that there were absolutely no public toilets within sight.

Another first impression was that of the hordes of young children who were war refugees. They roamed the streets calling to American soldiers with the words, “Hey GI, you give me money, you give me candy, you give me cigarettes.”

Local children

Pity the poor soldier who made the mistake of handing anything to a beggar. Once your hand reached into your pocket literally dozens of kids came from every doorway and shack to see if they could get a hand out. You were better off not giving them anything.

If you ignored their pleas they would say, “You number 10 GI.” If you gave them anything you were, “Number one”, which to them was the best.

Some of the children were trained as pick pockets and thieves. One youngster grabbed me by the arm spouting the usual “you gimme” this and “you gimme” that. All the while he was trying to unfasten my watch band in order to steal my watch. If they got the watch off your arm they ran faster than you could ever imagine and quickly disappeared into the crowded city streets.

I wouldn't say I enjoyed my work as a clerk typist but it beat marching through the jungle with a 50-pound pack on your back. The days were long 12-14 hours, and every two weeks we got a day off. We usually slept on our day off.

Most of our clothes washing, ironing, boot shining and bed making were done by a Vietnamese “hooch maid.” These were usually young teenage girls who came to work every day around 7 am and worked until 4 pm. They usually did the work for four or five soldiers at a time and for this we paid them five dollars a month each. All the clothes washing was done by hand in aluminum tubs using hand soap. The clothes were dried by hanging them on the barbed wire. After they dried the girls would iron the uniforms.

Hooch Maid

A female “hooch maid” could make more in one month than a captain in the South Vietnamese Army but due to their male-dominated culture she had to turn over all her earnings to the “man of the house.”

Not being stupid, the men would usually find jobs with the Americans for their wives and daughters. As a result the father or husband could afford to buy a motorcycle and ride around town all day having fun with his buddies. Often they would look like a gang of Hells Angels as they zipped past you on their 90 cc motorbikes.

With few exceptions the headquarters company preferred hiring women to do a lot of the menial tasks around the compound. They didn't trust the men since there was the possibility that they could be Viet Cong in disguise. If men were allowed on the compound to work they were usually under American guard or operated approved businesses such as a barber shop.

The “hooch maids” were usually very good Catholics who might flirt with you but would never date an American soldier. The girls would usually go to morning mass before coming to work and evening mass before going home. They spent most of Sunday at church.

We did have a few Buddhists working for us and the Catholic Vietnamese usually didn't treat them very well. Being young and not worldly wise we were mystified by their religious attitudes towards each other.

With more and more soldiers coming over to Vietnam to participate in the war effort there developed an acute need for sleeping quarters for the men. The brass decided to replace the tents with two story wood construction buildings that were open to the elements excepting for the bug screens on all four sides of the building.

Now the openness of the buildings might have been ok in the Mekong Delta where the temperatures were quite warm. However at our latitude our winter temperatures got into the low 50's F. and you needed wool blankets at night to keep warm. Also, taking a shower in cold water outside in those temperatures was nothing to look forward to.

The General's House

The officers didn't have to contend with the weather like the enlisted men did. Most of the officers lived in 12' x 50' mobile homes brought in by ship to Qui Nhon Harbor. The residents of this nice little mobile home community also included the nurses from the base hospital.

The commanding general of the Qui Nhon district lived in great luxury compared to enlisted men. He had a very large air-conditioned home with a dining room that could seat ten or more people. He also ate off china using silverware while we had to put up with the incredibly bad food in the mess hall. I lost over 30 pounds in the first six months of my tour due to the poor quality of food and beverages.

To supplement our diet we would often go to the Post Exchange (PX) and stock up on “camper's food”. This included cans of beef stew with a small sterno can attached to the bottom so you could literally cook the food while in the can.

We also requested from home bottles of Tabasco Sauce and other spices that we would use to give some flavor to the food.

My disdain for Army food changed after my first assignment in the field where only

C-Rations and K-Rations were available. K-Rations were actually surplus World War II field rations that had not stood the test of time well.

Yes, I got my butt assigned to a combat field unit. Some genius at headquarters noted my Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) was that of a radio operator (O5B2H). Also, they found out I functioned as an instructor when I was at Fort Ord, California.

At that moment in time the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) needed someone to teach the soldiers of the 9

th ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) Division how to operate US Army combat radios such as the

PRC-10,

PRC-25, and the base station radio AN/GRC-87.

I think I was selected for the job not because I was the most qualified but because everyone above me had more rank and didn't want to risk life and limb out in the jungles of South Vietnam.

So, I was temporarily assigned (TDE) to the Qui Nhon MACV unit (Advisory Team 27) that was assisting the South Vietnamese soldiers of the 9

th ARVN Division. These assignments often lasted for several weeks and in between I would return to my regular assignment at the headquarters company.

The American advisors working with MACV were happy to have me with their team. I was fortunate to have career officers and NCOs who felt we could win the war and that their job with the Vietnamese was an honorable one. Remember, this is still 1966 and the antiwar sentiments and poor troop morale and drug abuse of later years had yet to make an appearance in Qui Nhon.

My job teaching the Vietnamese was strictly OJT (On The Job Training). Fortunately it was made easier by a Vietnamese interpreter who was assigned to me. MACV also gave me temporary command rank of sergeant E-5 in order to work with the Vietnamese troops. Unfortunately it didn't come with any increase of pay from my more permanent SP4 (E-4) status.

Two soldiers of the 9th ARVN Division

The Vietnamese soldiers were not stupid by any means. They were well aware of the fact that in any battle the Viet Cong would try to shoot the radio man first along with anyone carrying a machine gun. But they were ordered to take the training and to disobey their superiors would bring down some fearful punishment on their heads.

After some perfunctory training in radio operations the Vietnamese officers declared their men ready to operate the radios in the field. My advice for additional training fell on deaf ears and we were ordered to do a day-long field exercise despite the misgivings of me and the other American advisors.

For our field exercise they trucked us from the outskirts of Qui Nhon west along QL 19 (Route 19) and the Song Ha Thanh River to about 20 kilometers from the American base at An Khe and near the village of Bin Khe. QL 19 was a major artery for supplies heading from the port city of Qui Nhon then approximately 60 kilometers to An Khe and further on to Pleiku and the Cambodian border.

The Viet Cong would frequently ambush convoys along QL 19 and they would also blow up the POL pipe line that brought petroleum products to the American bases. Our job was to assist the 9

th ARVN soldiers in clearing out a suspected Viet Cong controlled area. It had been relatively quiet for weeks prior to this day and we expected no opposition. It was just supposed to be a learning exercise.

This was my first time in the “boonies” and I was a little apprehensive about how the men I trained would perform and more importantly, how I would perform.

Another worry I had was how the South Vietnamese were equipped. Except for the radios all their weapons were surplus World War II items. They had M1 Garand rifles, M1 and M2 carbines, 45 cal. grease guns, and 30 cal. machine guns. On top of this even the American advisors had these same types of weapons. There was not an M-14 or M-16 to be had and I wondered how well the Viet Cong were equipped and would we be at a disadvantage in a firefight.

Despite the reassurances of my American comrades I shouldn't have been concerned. As I was to find out later the Viet Cong in our area were mostly equipped with surplus bolt action rifles of Chinese or Czech manufacture. In 1966 only the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regulars in our area had AK-47 assault rifles. Fortunately for us there were no NVA in our area that day.

Our walk through the woods that day was relatively uneventful with the platoons of men fanning out to search an assigned area on the map. I followed along with my interpreter and another American sergeant and from time to time I assisted my Vietnamese radio man in the operation of the PRC-25 combat radio. It was important that all the patrols maintain radio contact with each other and with the American and Vietnamese commanders on the scene.

I had been advised to get extra long mike cords for the radios, which I did. In that way we could use the radios while keeping a safe distance from the radio man who by now stood out like a big bull's eye to the Viet Cong rifles. This sounds callous but the American attitude was, “better them than us.”

One of our patrols stumbled on the enemy and we began to hear shots and radio chatter immediately picked up. We were about to move to a flanking position when I began to hear a buzzing sound nearby and puffs of dirt began sprouting in an area in front of us.

I was fascinated by what I heard and saw to the point that I lost all track of where I was. I turned around to say something to the American sergeant who was with our patrol and everyone had vanished. They had gone to cover behind some trees several yards back and they were all yelling at me at the top of their lungs.

The yelling was both in English and Vietnamese and you couldn't understand a word. What they were saying was, “Get down you idiot, take cover, they are shooting at you.”

In one of those classic movie double takes I looked at my comrades, looked at the puffs of dirt now sprouting all around me and I just dove for the deck and made the fastest low crawl of my life to the line of trees behind me.

I got a royal ass chewing from my American sergeant on how stupid I was and some rather strange looks and head shaking from the Vietnamese soldiers. It seems that my presence in front of them prevented my unit from returning fire. Not an auspicious beginning for my first time in combat.

The shooting was over as fast as it had begun thanks to some helicopter gunships from An Khe that one of the American advisors had called in by radio. We also received artillery support from one of the fire support bases (FSB) along Route 19. As a result the Viet Cong had just melted into the jungle with just a few bodies left behind and several blood trails. We suffered no casualties from the shooting except for one of the advisors who was literally trampled by 9

th ARVN soldiers trying to get away from the shooting. He had black and blue marks where the soldiers trampled him as well as foot prints on his uniform. Needless to say he wasn't happy and told the ARVN commander about it in very strong language.

By now it was getting late and we didn't want to be in that area after sundown. It was a fact that the Viet Cong ruled the area after dark and only air superiority, in the day light hours, gave us the upper hand. We packed up our equipment and hot footed it back to the trucks for the return trip to Qui Nhon. So ended my first day in combat and after checking my equipment on the way back it dawned on me that I had not fired a single shot.

Read part 1 -

Welcome to Vietnam

Follow us on

Copyright © VietnamGear.com. All

rights reserved. This material is intended solely for internal use within VietnamGear.com.

Any other reproduction, publication or redistribution of this material without the

written agreement of the copyright owner is strictly forbidden and any breach of

copyright will be considered actionable